Battle of Flers–Courcelette

| Battle of Flers–Courcelette | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Somme of the First World War | |||||||||

Battle of the Somme 1 July – 18 November 1916 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Douglas Haig Ferdinand Foch Émile Fayolle Henry Rawlinson Hubert Gough |

Crown Prince Rupprecht Fritz von Below | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Sixth Army Fourth Army (11 divisions, 49 tanks) Reserve Army | 1st Army | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 29,376 | (part of 130,000 casualties in September) | ||||||||

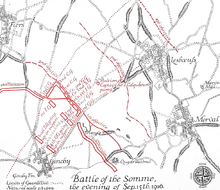

The Battle of Flers–Courcelette ([flɛʁ kuʁsəlɛt], 15 to 22 September 1916) was fought during the Battle of the Somme in France, by the French Sixth Army and the British Fourth Army and Reserve Army, against the German 1st Army, during the First World War. The Anglo-French attack of 15 September began the third period of the Battle of the Somme but by its conclusion on 22 September, the strategic objective of a decisive victory had not been achieved. The infliction of many casualties on the German front divisions and the capture of the villages of Courcelette, Martinpuich and Flers had been a considerable tactical victory.

The German defensive success on the British right flank made exploitation and the use of cavalry impossible. Tanks were used in battle for the first time; the Canadian Corps and the New Zealand Division fought their first engagements on the Somme. On 16 September, Jagdstaffel 2, a specialist fighter squadron, began operations with five new Albatros D.I fighters, which had a performance capable of challenging British and French air supremacy for the first time in the battle.

The British attempt to advance deeply on the right and pivot on the left failed but the British gained about 2,500 yd (1.4 mi; 2.3 km) in general and captured High Wood, moving forward about 3,500 yd (2.0 mi; 3.2 km) in the centre, beyond Flers and Courcelette. The Fourth Army crossed Bazentin Ridge, which exposed the German rear-slope defences beyond to ground observation. On 18 September, the Quadrilateral, where the British advance had been frustrated on the right flank, was captured.

Arrangements were begun immediately to follow up the success which, after supply and weather delays, began on 25 September at the Battle of Morval, continued by the Reserve Army next day at the Battle of Thiepval Ridge. September was the most costly month of the battle for the German armies on the Somme, which suffered about 130,000 casualties. Combined with the losses at Verdun and on the Eastern Front, the German Empire was brought closer to military collapse than at any time before the autumn of 1918.

Background

[edit]Strategic developments

[edit]Franco-British

[edit]At the beginning of August, optimistic that the Brusilov Offensive (4 June to 20 September) on the Eastern Front in Russia, would continue to absorb German and Austro-Hungarian reserves and that the Germans had abandoned the Battle of Verdun, General Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France, advocated to the War Committee in London, that pressure be kept on the German armies in France for as long as possible. Haig had hoped that the delay in producing tanks had been overcome and that enough would be ready in September.[1] Despite the small numbers of tanks available and the limited time for the training of their crews, Haig planned to use them in the mid-September battle being planned with the French, in view of the importance of the general Allied offensive being conducted on the Western Front in France, on the Italian front by Italy against the Austro-Hungarians and by General Aleksei Brusilov in Russia, which could not continue indefinitely. Haig believed that the German defence of the Somme front was weakening and that by mid-September might collapse altogether.[1]

By September, Ferdinand Foch the commander of Groupe d'armées du Nord (GAN) and co-ordinator of the Somme offensive, had stopped trying to get the armies on the Somme (Tenth, Sixth, Fourth and Reserve) to attack simultaneously, which had proved impossible and instead make separate sequenced attacks, successively to envelop the German defences. Foch wanted to increase the size and tempo of attacks, to weaken the German defence and achieve rupture, a general German collapse. Haig had been reluctant to participate in August, when the Fourth Army was not close enough to the German third position to make a general attack practicable. The main effort was being made north of the Somme by the British and Foch had to acquiesce, while the Fourth Army closed up to the third position.[2] To help the Fourth Army, the Reserve Army was to resume attacks against Thiepval and begin attacks into the Ancre river valley; the Fourth Army was to capture the German intermediate and second positions from Guillemont to Martinpuich and then the third position from Morval to le Sars, as the Sixth Army attacked the intermediate line from Le Fôret to Cléry, then the third position from the Somme to Rancourt. On the south side of the river, the Tenth Army would commence its postponed attack from Barleux to Chilly.[3]

German

[edit]On 28 August, General Erich von Falkenhayn, the Chief of the General Staff of Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, supreme army command), simplified the German command structure on the Western Front by establishing two army groups. Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht controlled the 6th Army, 1st Army, 2nd Army and 7th Army, from Lille to the boundary of Heeresgruppe Deutscher Kronprinz, from south of the Somme battlefield to beyond Verdun. Armeegruppe Gallwitz-Somme was dissolved and General Max von Gallwitz reverted to the command of the 2nd Army.[4] The emergency in Russia caused by the Brusilov Offensive, the entry of Romania into the war and French counter-attacks at Verdun, put further strain on the German army. Falkenhayn was sacked from the OHL on 28 August and replaced by Hindenburg and Ludendorff. The "Third OHL" ordered an end to attacks at Verdun and the despatch of troops to Romania and the Somme front.[5]

Tactical developments

[edit]

Flers is a village 9 mi (14 km) north-east of Albert, 4 mi (6.4 km) south of Bapaume, to the east of Martinpuich, west of Lesbœufs and to the north-east of Delville Wood. The village is on the D 197 from Longueval to Ligny Thilloy. In 1916, the village was defended by the Switch Line, Flers Trench on the western outskirts, Flea Trench and Box and Cox were behind the village in front of Gird Trench and Gueudecourt. Courcelette is near the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road, 7 mi (11 km) north-east of Albert, to the north-east of Pozières and south-west of Le Sars.[6]

Since 1 July, the BEF GHQ tactical instructions issued on 8 May had been added to but without a general tactical revision.[7] Attention had been drawn to matters which had been neglected in the heat of battle, such as the importance of infantry skirmish lines being followed by small columns, captured ground being mopped up, avoiding the tendency to rely on hand-grenades (bombs) at the expense of the rifle, consolidation of captured ground, the benefit of machine-gun fire from the rear, the use of Lewis guns on the flanks and in outposts and the value of Stokes mortars for close-support.[8][9] The wearing-out battles since late July and events elsewhere, led to a belief that the big Allied attack planned for mid-September would have more than local effect.[10]

A general relief of the German divisions on the Somme was completed in late August; the British assessment of the number of German divisions available as reinforcements was increased to eight. GHQ Intelligence considered a German division on the British front was worn-out after 4+1⁄2 days and that German divisions had to spend an average of twenty days in the line before relief. Of six more German divisions moved to the Somme by 28 August, only two had been known to be in reserve, the other four having been moved from quiet sectors without warning.[10]

Hindenburg issued new tactical instructions in Grundsätze für die Führung in der Abwehrschlacht im Stellungskrieg ("Principles of Command for Defensive Battles in Positional Warfare") which ended the emphasis on holding ground at all costs and counter-attacking every penetration. The purpose of the defensive battle was defined as allowing the attacker to wear out their infantry, using methods that conserved German infantry. Manpower was to be replaced by machine-generated firepower, using equipment built in a competitive mobilisation of domestic industry under the Hindenburg Programme, the policy rejected by Falkenhayn as futile, given the superior resources of the coalition fighting the Central Powers. Defensive practice on the Somme had already been changing towards defence in depth, to nullify Anglo-French firepower and the official adoption of the practice marked the beginning of modern defensive tactics. Ludendorff also ordered the building of the Siegfriedstellung, a new defensive system 15–20 mi (24–32 km) behind the Noyon Salient (which became known as the Hindenburg Line) to make possible a withdrawal while denying the Franco-British the chance to fight a mobile battle.[11]

Since July German infantry had been under constant observation from aircraft and balloons, which directed huge amounts of artillery-fire accurately onto their positions and made many machine-gun attacks on German infantry. One regiment ordered men in shell-holes to dig fox-holes or cover themselves with earth for camouflage and sentries were told to keep still to avoid being seen.[12] The German air effort in July and August had mostly been defensive, which led to much criticism from the infantry and ineffectual attempts to counter Anglo-French aerial dominance, dissipating German air strength to no effect. Anglo-French artillery observation aircraft were considered brilliant, annihilating German artillery and attacking infantry from very low altitude, causing severe anxiety among German troops, who treated all aircraft as Allied and came to believe that British and French aircraft were armoured.[13]

Redeployment of German aircraft backfired, many losses being suffered for no result, which further undermined relations between the infantry and Die Fliegertruppen des deutschen Kaiserreiches (Imperial German Flying Corps). German artillery units preferred direct protection of their batteries to artillery observation flights, which led to more losses as the German aircraft were inferior to their opponents as well as outnumbered.[13] Slow production of German aircraft exacerbated equipment problems and German air squadrons were equipped with a motley of designs until the arrival in August of Jagdstaffel 2 (Hauptmann [Captain] Oswald Boelcke), equipped with the Halberstadt D.II, which began to restore a measure of air superiority in September and the first Albatros D.Is, which went into action on 17 September.[14]

The tank

[edit]

Before 1914, inventors had designed armoured fighting vehicles and one design had been rejected by the Austro-Hungarian army in 1911. In 1912, Lancelot de Mole, submitted plans to the War Office for a machine which foreshadowed the tank of 1916, that was also rejected and in Berlin an inventor demonstrated a land cruiser in 1913. By 1908, the British army had adopted vehicles with caterpillar tracks to move heavy artillery and in France, Major Ernest Swinton, (Royal Engineers) heard of the cross-country, caterpillar-tracked Holt tractor in June 1914. In October, Swinton thought of a machine-gun destroyer that could cross barbed wire and trenches and discussed it at GHQ with Major-General George Fowke, the army chief engineer, who passed this on to Lieutenant-Colonel Maurice Hankey, the Secretary of the War Council. Little interest had been shown by January 1915. Swinton persuaded the War Office to set up an informal committee which in February 1915 watched a demonstration of a Holt tractor pulling a weight of 5,000 lb (2,300 kg) over trenches and barbed wire, the performance of which was judged unsatisfactory.[15]

Independent of Swinton, Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, had in October 1914, asked for an adaptation of a 15-inch howitzer tractor for trench crossing. In January 1915, Churchill had written to the Prime Minister on the subject of an armoured caterpillar tractor to crush barbed wire and cross trenches. On 9 June, a vehicle with eight driving wheels and bridging gear was demonstrated to the War Office committee. The equipment failed to cross a double line of trenches 5 ft (1.5 m) wide and the experiment was abandoned. In parallel to these explorations, on 19 January 1915, Churchill ordered Commodore Murray Sueter, Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) to conduct experiments with steamrollers and in February, Major Thomas Hetherington RNAS, showed Churchill designs for a land battleship. Churchill set up a Landships Committee, chaired by Eustace Tennyson d'Eyncourt, the Director of Naval Construction, to oversee the creation of an armoured vehicle to crush wire and cross trenches.[16]

In June 1915, Sir John French, commander of the BEF found out about the ideas put forward by Swinton for caterpillar machine-gun destroyers. French sent the memoranda to the War Office, which in late June began to liaise with the Landships Committee at the Admiralty and specified the characteristics of a vehicle. Churchill had relinquished his post in the War Committee but lent his influence to the experiments and building of the tanks. By August, Swinton was able to co-ordinate the War Office specifications for the tanks, Admiralty design efforts and manufacture by the Ministry of Munitions.[a] An experimental vehicle built by Fosters of Lincoln was tested in secret at Hatfield on 2 February 1916 and the results were considered so good that 100 more vehicles of the mother design and a prototype of the Mark I tank were ordered.[18]

In March 1916, Swinton was given command of the new Heavy Section, Machine-Gun Corps, raised with manpower from the Motor Machine Gun Training Centre at Bisley, with an establishment of six companies with 25 tanks each, crewed by 28 officers and 255 men. Training began in great secrecy in June at Elveden in Suffolk, as soon as the first Mark I tank arrived. Two types of Mark I tank had been designed, male tanks, with a crew of eight, two 6-pounder guns and three Hotchkiss 8 mm machine-guns, a maximum speed of 3.7 mph (6.0 km/h) and a tail (two wheels at the rear to help with steering and to reduce the shock of crossing broken ground). Female tanks were similar in size, weight, speed and crew and were intended to defend the males against an infantry rush, with their armament of four Vickers machine guns, a Hotchkiss machine-gun and a much larger allotment of ammunition.[18]

Prelude

[edit]Early-September attacks

[edit]Tenth Army

[edit]

The French Tenth Army attacked south of the Somme on 4 September, adding to the pressure on the German defence, which had been depleted by the attritional fighting north of the Somme since July. (Military units in this section are French unless specified.) The original German front position ran from Chilly, north to Soyécourt then along the new German first line north to Barleux, which had been established after the Sixth Army advances in July. Five German divisions held the front line which ran northwards through the fortified villages of Chilly, Vermandovillers, Soyécourt, Deniécourt, Berny-en-Santerre and Barleux. A second line of defence ran from Chaulnes (behind woods to the west and north and the château park, from which the Germans had observation over the ground south of the Flaucourt plateau), Pressoir, Ablaincourt, Mazancourt and Villers-Carbonnel.[19]

The Tenth Army had fourteen infantry and three cavalry divisions in the II, X and XXXV corps but many of their divisions had been transferred from Verdun and were understrength. The attack took place from Chilly north to Barleux, intended to gain ground on the Santerre plateau, ready to exploit a possible German collapse and then to capture crossings over the Somme south of Péronne. A four-stage advance behind a creeping barrage was planned, although reinforcements of artillery and ammunition were not available, due to the demand for resources at Verdun and north of the Somme.[20]

Much of the destructive and counter-battery bombardment in the X and XXXV corps sectors was ineffective, against defences which the Germans had improved and reinforced with more infantry. After six days of bombardment, the attack by ten divisions began on a 17 mi (27 km) front. The five German divisions opposite were alert and well dug-in but X Corps captured Chilly and part of the woods in the centre of the corps front. The corps was checked on the left at Bois Blockhaus Copse, behind the German front line. In XXXV Corps in the centre, the 132nd Division briefly held Vermandovillers and the 43rd Division advanced from Bois Étoile and took Soyécourt.[21]

The II Corps attack failed on the right flank, where German troops managed to hold the front line, the II Corps advanced in the north; at Barleux, the 77th Division was obstructed by uncut wire and the advanced troops were cut off and destroyed. German troops in front line dugouts that had not been mopped-up, had emerged and stopped the supporting waves in no man's land. More ground was taken, preparatory to an attack on the second objective but the offensive was suspended on 7 September after large German counter-attacks. The French took 4,000 prisoners and Foch doubled the daily allotment of ammunition to capture the German second position. From 15 to 18 September, the Tenth Army attacked again and captured Berny, Vermandovillers, Déniecourt and several thousand prisoners.[22]

Sixth Army

[edit]The Sixth Army was reinforced near the river on 3 September, by XXXIII Corps with the 70th and 77th divisions astride the river and VII Corps with the 45th, 46th, 47th and 66th divisions on the left. XX Corps on the left flank of the Sixth Army was relieved by I Corps, with the 1st and 2nd divisions and several fresh or rested brigades were distributed to each corps. Control of the creeping barrage was delegated to commanders closer to the battle and a communications system using flares, Roman candles, flags and panels, telephones, optical signals, pigeons and message runners was set up to maintain contact with the front line. Four French divisions attacked north of the Somme at noon on 3 September. Cléry was subjected to a machine-gun barrage from the south bank and VII Corps captured most of the village, much of the German position along the Cléry–Le Forêt road and Le Forêt village. On the left, I Corps advanced 1 km (0.62 mi), quickly occupied high ground south of Combles and entered Bois Douage.[23]

On 4 September, German counter-attacks at the Combles ravine stopped the French advance towards Rancourt but the French consolidated Cléry and forwarded to the German third position. The British took Falfemont Farm on 5 September and linked with the French at Combles ravine. French patrols captured Ferme de l'Hôpital 0.5 mi (0.80 km) east of Le Forêt and reached a ridge behind the track from Cléry to Ferme de l'Hôpital, which forced the Germans to retire to the third position in some confusion, XX Corps taking 2,000 prisoners.[24] VII Corps took all of Cléry and met XXXIII Corps on the right, which had captured Ommiécourt in the marshes south of the village, taking 4,200 prisoners, as French parties reached the German gun-line. An attack by I Corps failed on 6 September and attacks were delayed for six days, as the difficulty in supplying such a large force on the north bank was made worse by rain.[25]

Attempts by Foch and Fayolle to exploit the success before the Germans recovered failed because of the days lost to rain, the exhaustion of the I and VII corps, the lengthening of the Sixth Army front and its divergence from the line of the Fourth Army advance. A defensive flank was made on the left along Combles ravine by I Corps. V Corps was moved out of reserve and for the first time, Foch issued warning orders for the Cavalry Corps to prepare to exploit a German collapse. Transport difficulties became so bad that General Adolphe Guillaumat, the I Corps commander, ordered all stranded vehicles to be thrown off the roads and supply to continue in daylight, despite German artillery-fire, ready for the resumption of the attack on 12 September.[26]

On 12 September, XXXIII Corps attacked towards Mont St Quentin and VII Corps attacked Bouchavesnes, taking the village and digging in facing Cléry and Feuillaucourt. I Corps took Bois d'Anderlu and broke through the German defences near Marrières Wood, before attacking northwards towards Rancourt and Sailly-Saillisel. On 13 September, I Corps closed on Le Priez Farm and VII Corps defeated several big German counter-attacks. Next day, the attacks of VII and XXXIII corps were stopped by mud and German defensive fire but I Corps managed to take Le Priez Farm. Attacks were suspended again to bring up supplies and relieve tired troops, despite the big British attack due on 15 September. Frégicourt, which overlooked part of the area to be attacked by the British, was still held by the Germans. Although Foch wanted to keep pressure on the Germans south of the river, supply priority was given to the Sixth Army; the Tenth Army met frequent German counter-attacks near Berny, which took some ground and was not able to resume its attacks.[27]

German preparations

[edit]| Date | Rain mm |

Temp °F/°C |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 0 | 59°–43°/15°–6° | cool haze |

| 16 | 0 | 66°–41°/19°–5° | fine sun |

| 17 | 2 | 63°–45°/17°–7° | — |

| 18 | 13 | 63°–46°/17°–8° | rain |

| 19 | 3 | 55°–43°/13°–6° | wet wind |

| 20 | 1 | 61°–48°/16°–9° | rain |

| 21 | 0.1 | 59°–48°/15°–9° | dull rain |

| 22 | 0 | 64°–41°/18°–5° | mist |

Falkenhayn had been superseded on 29 August and the cessation of German attacks at Verdun was ordered by the new Oberste Heeresleitung comprising the Chief of the General Staff, Field Marshal (Generalfeldmarschall) Paul von Hindenburg and Generalquartiermeister General Erich Ludendorff. Reinforcements ordered to the Somme front by the new commanders reduced the German inferiority in guns and aircraft during September. The field artillery was able to reduce its barrage frontages from 400 to 200 yd (370 to 180 m) per battery and increased the accuracy of its bombardments by using one air artillery flight per division. Colonel (Oberst) Fritz von Loßberg, Chief of Staff of the 2nd Army, was also able to establish Ablösungsdivisionen (relief divisions) 10–15 mi (16–24 km) behind the battlefield, ready to replace the front divisions. The 2nd Army was able to mount bigger and more frequent counter-attacks, making the Anglo-French advance slower and more costly.[29]

About five German divisions were opposite the Fourth Army, with the II Bavarian Corps (Generalleutnant Otto von Stetten), which had arrived on the Somme front from Lille in the 6th Army area, at the end of August. The 3rd Bavarian Division held the line from Martinpuich to High Wood and the 4th Bavarian Division the ground from High Wood to Delville Wood. The line eastwards was held by the 5th Bavarian Division of the III Bavarian Corps (General der Kavallerie Ludwig von Gebsattel), which had arrived from Lens, also in the 6th Army area, ten days previous. The 50th Reserve Division was in reserve behind the 3rd Bavarian Division, having been transferred from Armentières and the 6th Bavarian Division en route from the Argonne, was assembling behind the 4th and 5th Bavarian divisions. There were three trench systems, the front line being in Foureaux Riegel (Switch Trench) about 500 yd (460 m) across no man's land, along the south face of Bazentin ridge. About 1,000 yd (910 m) back on the far side of the ridge lay Flers Riegel (Flers Trench to the British) in front of the village of Flers and another 1,500 yd (1,400 m) back lay Gallwitz Riegel (Gird Trench) in front of Gueudecourt, Lesbœufs and Morval.[30]

The Entente tactic of attacking strictly limited objectives had made the German defence more difficult and the constant Anglo-French artillery bombardments turned the German defences into crater-fields. Dugouts were caved in, barbed-wire entanglements were vapourised and trenches obliterated. German infantry took to occupying shell-holes in two- and three-man teams, about 20 yd (18 m) apart. Supporting and reserve units further back used shell-holes and any cover that could be found for shelter. Attempts to link shell-hole positions with trenches were abandoned because they were easily visible from the air and Entente artillery-observation crews directed bombardments on them. When attacks commenced, German infantry usually moved forward from such visible positions and created an advanced line of occupied shell-holes but this was often overrun during an attack. British and French infantry then set up a similar defence in shell-holes about 100 yd (91 m) beyond, before the German infantry in reserve could begin a hasty counter-attack (Gegenstoß). The Germans tried to resort to occasional methodical counter-attacks (Gegenangriffe) on a broad front, to recapture tactically valuable areas but most of these failed too, because of insufficient men, artillery and ammunition.[31]

The German commanders expected that the British and French would continue the Somme offensive, given their superiority in numbers and equipment. In early September, Gruppe Marschall (General Wolf Freiherr Marschall von Altengottern) the headquarters of the Guard Reserve Corps, reported an increase in British activity and much artillery-fire on the front from Thiepval to Leuze Wood. The timing of the new attack was unknown and the relief of exhausted divisions continued. (Some German prisoners taken on the III Corps front on 15 September claimed that they had been warned of land cruisers with thick armour the day before. Prisoners taken near Bouleaux Wood said that Spitzgeschoß mit Kern (S.m.K., bullet with core) ammunition had been issued and that grinding noises had been heard from behind the British lines, which was taken to be mining but the "sinister, noisy sounds" had stopped during the night of 14/15 September.)[32]

British preparations

[edit]

Planning for the offensive began in August and continued into September, while XIV Corps (Lieutenant-General the Earl of Cavan) was engaged on the right flank and XV Corps (Lieutenant-General John Du Cane) and III Corps (Lieutenant-General William Pulteney) were fighting for Delville and High woods. The attacks on the woods added to the burden on transport, engineer, pioneer and labour units. Repairs to damage caused by German artillery-fire diverted effort from shelter being built for fresh divisions assembling behind the front; communications were improved and new battery positions and headquarters erected, new supply dumps created, water supplies increased and carrying services organised into the ground due to be captured. The Fourth Army chief engineer, Major-General Reginald Buckland, had labour and engineer stores for road and track building and repair brought forward in preference to work on the Fourth Army (General Sir Henry Rawlinson) rear area, which was helped by new railheads at Albert and Fricourt. A broad-gauge line had been pushed up to Maricourt by 10 September and a metre-gauge track was almost as far forward as Montauban.[33]

The Fourth Army artillery was reinforced by five 60-pounder batteries, a 6-inch howitzer battery, two 9.2-inch howitzer batteries and the field artillery of divisions that had recently arrived in France. Rawlinson wanted as much artillery as possible moved forward before the attack to avoid moves once the attack began and the batteries to move forward first were given portable bridges. XIV Corps had 244 18-pounder guns and 64 4.5-inch howitzers, four heavy siege artillery groups with a 15-inch howitzer, two 12-inch howitzers, twenty 9.2-inch, eight 8-inch and forty 6-inch howitzers, two 9.2-inch guns, twenty-eight 60-pounders and four 4.7-inch guns. XV Corps had 248 18-pounders, seventy-two 4.5-inch howitzers and five heavy and siege groups, III Corps had 228 18-pounders, sixty-four 4,5-inch howitzers and five heavy and siege groups, which amounted to a field gun or howitzer for every 10 yd (9.1 m) of front and a heavy piece every 29 yd (27 m). In the Reserve Army, the Canadian Corps had three heavy groups and the 3rd Canadian Division, forming the defensive flank, was given six field artillery brigades, with two in corps reserve for contingencies.[34]

Experience had shown that it took six hours for orders to pass from corps headquarters to company commanders and it was now considered of great importance to issue warning orders, to give time for reconnaissance and preparation by the artillery and infantry. It had also been found that corps headquarters had become aware of the situation from contact-patrol aircrew reports, while brigade headquarters were ignorant of events and arrangements for the swift transmission of information forwards were made. The signalling system for a larger number of contact-patrol aircraft was established and sites for new signal stations on the ground to be attacked were chosen beforehand. If the German defences collapsed it was considered impossible to lay cables quickly and that only one telegraph from brigade, to division to corps could reasonably be expected. Relays of runners, cyclists, horse riders and motorcyclists were to be used as a supplement, with messenger-pigeons to be used in an emergency. Wireless stations were attached to infantry brigades but transmissions were slow, uncertain, caused interference with other transmitters and were open to German eavesdropping.[35]

British plan

[edit]

The British attack was intended to break through of the main German defences on a 3.5 mi (5.6 km) front, beginning with timetabled limited objective attacks, generally to the north-east. These were ambitious objectives and Haig required preparations to be made for the exploitation of the infantry attack by an advance of the cavalry, should the German defence collapse. Rawlinson favoured a cautious operation with methodical attacks on the German defensive positions and set the German Switch line and its connecting defences in front of Martinpuich as the first objective (Green Line). The right flank of the XIV Corps was to capture the forward slopes of the high ground to the north-west of Combles, which required an advance of 1,000 yd (910 m) from the Quadrilateral to Delville Wood and a 600 yd (550 m) advance on the rest of the front.[36]

A second objective (Brown Line) took in the German third position covering Flers to be taken by the XV Corps and subsidiary defences from Flers to Martinpuich to be attacked by the III Corps, an advance of another 500–800 yd (460–730 m).[36] A third objective (Blue Line) was 900–1,200 yd (820–1,100 m) beyond, at the German third position and rear defences covering Morval and Lesbœufs to be taken by the XIV Corps and Flers village (XV Corps), the line extending to the west so that the III Corps advance would be 350 yd (320 m), encircling Martinpuich and closing up to German artillery positions near Le Sars. A fourth objective (Red Line) was set 1,400–1,900 yd (1,300–1,700 m) forward of the Blue Line and was beyond Morval and Lesbœufs, to be taken by the XIV Corps and Gueudecourt by the XV Corps, from where the two corps were to form a defensive flank, from Gueudecourt to the third position past Flers, facing north-west.[36]

The defensive flank to the north of Combles was to be extended by the right flank of XIV Corps onto slopes south-east of Morval and the French Sixth Army south of Combles was to advance to Frégicourt and Sailly-Saillisel to surround Combles from the south with a I Corps advance on Rancourt and Frégicourt to form the defensive flank; V Corps was to close up to St Pierre Vaast Wood as VII Corps attacked east of Bouchavesnes and XXXIII Corps attacked at Cléry. The III Corps on left of the Fourth Army was to link with the right flank of the Reserve Army, which at first was to conduct subsidiary operations but if the Fourth Army attack bogged down, the main effort might be transferred to the Reserve Army, to capture Thiepval and take up winter positions.[37]

The plan for the Reserve Army was issued on 12 September for the right flank of the Canadian Corps to attack with the III Corps to capture vantage points over the German defences from Flers to Le Sars and Pys. The 2nd Canadian Division was to attack on a 1 mi (1.6 km) front from its right flank to the Ovillers–Courcelette track, a 1,000 yd (910 m) to the edge of Courcelette and a 300 yd (270 m) advance on the left with the 3rd Canadian Division providing a flank guard. The Canadian infantry were to advance after the preliminary bombardment straight on to the objective, a continuation of the Green Line. The II Corps on the left flank was to exploit chances to take ground, especially to the south of Thiepval, where cloud gas was to be released and the 49th Division was to simulate an attack with a smoke screen. North of the Ancre, V Corps was to discharge smoke and raid two places.[37]

Zero hour was set for 6:20 a.m. British Summer Time (BST) 15 September. The Red Line was to be reached before noon, allowing for eight hours of daylight for the exploitation. Two cavalry divisions were swiftly to pass between Morval and Gueudecourt and after an all-arms force had established a defensive flank from Sailly-Saillisel to Bapaume, the rest of the Fourth Army could attack northwards and roll up the German defences. An exploitation force like that of 1 July was not assembled but the Cavalry Corps objective was high ground between Rocquigny and Bapaume and the German artillery areas from Le Sars to Warlencourt and Thilloy. The cavalry was to be supported by XIV and XV corps as quickly as possible. Railway lines that could be used to carry reinforcements, divisional and corps headquarters were to be attacked by cavalry. In an advance by all arms, priority would go to artillery moving forward to support the infantry attacks. When the Red Line was reached, the quick movement forward of the cavalry would take precedence, until the cavalry divisions had passed through, when light wagons carrying food and ammunition for the infantry would take priority. Movement of the cavalry needed strict control, lest a bottleneck develop and the re-building of roads and tracks was to commence as soon as the attack began, each division being given routes to work on.[37]

In the XIV Corps area on the right flank, the 56th (1/1st London) Division (Major-General C. P. A. Hull) was to form a defensive flank on the north-west slope of the Combles Ravine. The 6th Division (Major-General C. Ross) had been held up by the Quadrilateral 0.5 mi (0.80 km) to the north of Leuze Wood, which lay in front of the first objective. An advance by the 56th (1/1st London) Division past Bouleaux Wood would outflank the south end of the Quadrilateral and ease the advance of the 6th Division and that of the Guards Division (Major-General Geoffrey Feilding) further north across the ridge in front towards Morval and Lesbœufs to the north-east. Three tanks were to attack the Quadrilateral and just before zero hour, three columns of three tanks each, were to attack on the front of the Guards Division.[38]

Battle

[edit]Sixth Army

[edit]By 15 September the Sixth Army needed a pause after its attacks on 12 September to relieve worn-out troops and bring forward supplies. The artillery of I Corps supported the British XIV Corps attack at dawn and its infantry attacked at 3:00 p.m., beginning a bombing fight with the Germans at Bois Douage. Ground was gained north of Le Priez Farm but no progress was made at Rancourt. V Corps, to the east, failed to reach the south side of St Pierre Vaast Wood, VII Corps made no progress east of Bouchavesnes and XXXIII Corps straightened its front.[39] On 16 September, the Sixth Army conducted counter-battery fire in support of the British, with the infantry prepared to follow up if the Germans were forced into an extensive withdrawal.[40] (After 16 September, V Corps extended its right flank and VI Corps took over the VII Corps front. Preparations were made for a Franco-British attack on 21 September, which was postponed until 25 September by supply difficulties and the rain. Despite the reorganisation, I Corps made two surprise attacks late on 18 September, near Combles, which gained ground. German artillery-fire in the area was extensive and counter-attacks at Cléry during the night of 19/20 September, at Le Priez Farm and Rancourt during the morning and at Bouchavesnes later, were repulsed by the French only after "desperate" fighting. South of Bouchavesnes, a German attack was defeated by VI Corps.)[40]

Fourth Army

[edit]15 September

[edit]

On the right of XIV Corps, the 56th (1/1st London) Division ordered the 169th Brigade (Brigadier-General Edward Coke) to capture Loop Trench across the Combles ravine, defended by Reserve Infantry Regiment 28 of the 185th Division. The brigade was to keep contact with the French in the valley. During the night, a battalion dug jumping-off trenches parallel to Combles Trench below Leuze Wood and a tank drove up to the corner of the wood by dawn. The tank set off again just before 6:00 a.m. to reach the objective with the infantry and after twenty minutes the creeping barrage began. Infantry advanced with the right wing aiming at the junction of Combles and Loop trenches and escaped a German counter-barrage which was late and easily reached the objective.[41]

The tank was a great shock to the defenders and greatly assisted the attack. The attackers were now to swing right to capture Loop Trench and the Loop but crossfire from German machine-guns prevented this and the British began to bomb up Loop Trench and down Combles Trench, which took all day and was reinforced by another battalion and a party of bombers. The tank was knocked out near the Loop but the crew held off German bombers, inflicting many casualties, until it was set on fire five hours later and abandoned. When night fell, a block was set up in Combles Trench beyond the junction but in the Loop the British were 80 yd (73 m) short of the sunken road and an attack at 11:00 p.m. failed.[41]

The 167th Brigade (Brigadier-General George Freeth) was to advance northwards to lengthen the defensive flank through the top end of Bouleaux Wood to overlook Combles from the north-west, clear the rest of the wood and link with the 6th Division on the left in the valley beyond. The 168th Brigade would pass through to guard the right flank as Morval was being captured and rendezvous with the French at a crossroads beyond. A 167th Brigade battalion was to advance to the first objective, capturing the German front line trench in Bouleaux Wood and north to Middle Copse. On the right flank the battalion was to bomb downhill towards Combles and link with the 169th Brigade where the Loop joined the sunken road into the village. Two tanks were allotted but one lost a track on the drive to the assembly point in the west side of Bouleaux Wood. The second tank drove slowly towards Middle Copse at 6:00 a.m. attracting much return fire but the infantry attack was stopped by uncut wire and machine-guns, the barrage being ineffectual. No man's land was too narrow to risk a bombardment and the German front line was undamaged and hidden in undergrowth. The bombing attack south-east from the wood could not begin but on the left flank, the Londoners got into the front line and advanced close to Middle Copse; the tank had driven to the end of Bouleaux Wood and then ditched. German bombers attacked the tank and the crew retreated after they had all been wounded.[42][b]

When the 6th Division attacked on the left, the preliminary bombardments, even controlled by artillery observation aircraft, had left the Quadrilateral undamaged. The position was below the crest of ground beyond Ginchy in a depression, where the wire had been overgrown; the two brigadiers and the divisional commander thought that the preparation had failed. The 16th Brigade on the right was to capture the Quadrilateral with a battalion advancing on open ground from the south-west as a company bombed along the trench to the right. The second battalion in support was then to pass through the troops on the first objective and keep going to the third, where the final two battalions were to take Morval. The 71st Brigade on the left was to attack with two battalions to capture Straight Trench and then advance to the final objective supported by the other two battalions of the brigade. Three tanks with the division were to attack the Quadrilateral but two broke down before reaching the assembly point east of Guillemont. Ross asked for the tank lane in the creeping barrage to be closed and XIV Corps, which had considered this possibility, had the order passed to the XIV Corps Commander, Royal Artillery (CRA), Brigadier-General Alexander Wardrop; by chance, his orders to the 6th Division CRA were not followed.[44]

The surviving tank followed a railway line towards the Quadrilateral, passed through British troops at 5:50 a.m. and fired on them by mistake. An officer ran up to the tank through the gunfire and showed the crew the right direction. The tank turned north, drove parallel to Straight Trench and fired into it. The leading battalion of the 16th Brigade attacked at 6:20 a.m., advancing north-east and was quickly stopped by massed machine-gun fire, as was the second battalion which jumped off at 6:35 a.m. near the Leuze Wood–Ginchy road; bombers being stopped south-east of the Quadrilateral. The first two battalions of the 71st Brigade advanced over the front line, disappeared beyond the crest and overran an outpost but then the battalions were stopped by uncut wire and caught in machine-gun crossfire from the right and centre, which forced the survivors under cover, the tank, having already been riddled with bullets, returned when low on fuel.[44]

The Guards Division brigades had to assemble on devastated ground to avoid Ginchy which was frequently bombarded and on the right the 2nd Guards Brigade (Brigadier-General John Ponsonby) assembled to the south-east of the Ginchy–Lesbœufs road, the nine waves being only 10 yd (9.1 m) apart, with four platoons abreast over 400 yd (370 m) per battalion, for lack of room. The four battalions were to advance straight to the final objective. The 1st Guards Brigade (Brigadier-General Cecil Pereira) on the left was equally cramped, with both flanks bent back. One battalion was to reach the third objective and the second was to pass through to the final objective with one battalion guarding the left flank. The right group of three tanks arrived at the Ginchy–Lesbœufs road, to drive to the south end of the Triangle on the right flank as the centre group reached the north-west point but the three centre group tanks broke down en route. The left group of three tanks to advance west of Ginchy and move up Pint Trench and Lager Lane lost a tank on the assembly and the tenth tank to support the XV Corps attacking the pocket east of Delville Wood before zero hour broke down.[45]

The tanks advanced before zero hour but one failed to start, the rest lost direction and went east into the 6th Division area and then returned. Two tanks on the left began late, got lost and veered to the right; one ditched and the other ran short of fuel and returned, being the last tank operation with the Guards. The creeping barrage began prompt at 6:20 a.m. and the Guards followed 30 yd (27 m) behind but as the right of the 2nd Guards Brigade went north-east over the crest, massed machine-gun fire began from the Quadrilateral and Straight Trench. The Guards kept going but to the left of the intended direction, the two supporting battalions keeping close. A German party in a shell-hole position were rushed and bayoneted and the four battalions, mingled together, pressed on into the north end of the Triangle and Serpentine Trench to the left, where the wire had been well cut and the trenches devastated. I Battalion and II Battalion Bavarian Infantry Regiment 7 (BIR 7) had little artillery support and reported later that 20–30 RFC aircraft strafed them as the British advanced. Despite many casualties, the brigade overpowered the defenders and occupied part of the first objective by 7:15 a.m., the survivors of BIR 7 retiring on the III Battalion in Gallwitz Riegel.[46]

The 1st Guards Brigade was also met with machine-gun fire from Pint Trench and Flers Road; the two leading battalions hesitated momentarily before rushing the Germans and capturing several prisoners, four machine-guns and a trench mortar. The supporting battalion had advanced, veered north and overrun a shell-hole position, then arrived on the first objective simultaneously with the 2nd Brigade. The supporting battalion had strayed over the corps boundary, leaving the Germans in possession of Serpentine Trench on either side of Calf Alley. Attempts to sort out the units were made and it was thought that the third objective, 1,300 yd (1,200 m) on had been reached; a messenger pigeon was sent back, despite a Forward Artillery Observer (FOO) realising the mistake. XIV Corps HQ found that the mist and smoke had stopped contact patrol aircraft from watching the attack; the German artillery reply cut telephone lines and caused long delays in the arrival of runners. It was thought that the Guards had moved on the third objective on time at 8:20 a.m.; the 6th Division was known to have been stopped and the 56th (1/1st London) Division was on the first objective; nothing was known of the tanks.[47]

In the 56th (1/1st London) Division area, the 167th Brigade sent two companies to leapfrog through the leading battalion and take the third objective at 8:20 a.m. but it could not advance with the Germans still in Bouleaux Wood and even with the rest of the battalion, could only join the leading battalion in the trenches to the left of the wood. Two battalions of the 71st Brigade, 6th Division, attacked but were cut down by machine-gun fire, despite a re-bombardment of Quadrilateral Trench and Straight Trench. Parties from the 56th (1/1st London) Division got into a trench running south-east from the Quadrilateral, along with men from the 6th Division. At 9:00 a.m. Ross and Hull arranged for the 6th Division brigades to attack the Quadrilateral from the north, west and south at 1:30 p.m. as the 18th Brigade from reserve moved through the Guards Division and attacked Morval, based on the erroneous reports of the Guards' success. The 56th (1/1st London) Division was to capture Bouleaux Wood after another bombardment. Soon after the plans were laid, air reconnaissance reports reached Cavan with accurate information and the attack was cancelled. The 6th Division was ordered instead to take Straight Trench from the north at 7:30 p.m. after a bombardment by heavy artillery. The cancellation failed to reach the 1/8th Battalion Middlesex Regiment, which attacked on time and was shot down by machine-gunners of BIR 21 but by evening Middle Copse had been captured.[48][c]

The 2nd Guards Brigade collected bombers and captured the triangle by noon but a further advance, unsupported by the 6th Division, seemed impossible; a party of about 100 men advanced close to the third objective just below the Ginchy–Lesbœufs road. A battalion of the 1st Guards Brigade had advanced from Ginchy at 7:30 a.m. to support the advance to the third objective and kept direction to the north-east, advancing in artillery formation (a lozenge shape) and was fired on from part of Serpentine Trench. The battalion moved into line and charged, got a foothold in the trench, bombed outwards and gained touch with the battalions on the flanks, capturing the rest of the first objective. The 1st Guards Brigade battalions had reorganised, realised that they were short of the third objective, attacked again into a German bombardment and reached part of the second objective north of the corps boundary by 11:15 a.m. taking prisoner two battalion headquarters of BIR 14. Some troops joined with men from the 14th (Light) Division (Major-General Victor Couper); the attackers reported that they were on the third objective and sent back messages but contact patrol crews reported that the XIV Corps divisions were nowhere near the third objective. Late on the afternoon, BIR 7 counter-attacked and pushed a Guards party back from the Triangle but a second attack was repulsed with small-arms fire. All attacks except that of the 6th Division were cancelled until 16 September but the heavy artillery bombardment went over the crest and fell beyond the Quadrilateral. Two companies were to attack from near Leuze Wood and two down Straight Trench from the Triangle at 7:30 p.m. but only a 100 yd (91 m)-length of Straight Trench was captured.[50]

In the XV Corps area, on the left of the main attack, 14 of the 18 tanks in the area reached their jumping-off points, ready to attack Flers. The 14th (Light) Division attacked the small German salient east of Delville Wood with three tanks and two infantry companies; two of the tanks broke down and tank D1 advanced at 5:15 a.m. from Pilsen Lane, the bombers following a few minutes later. The Germans had been withdrawing and the tank gunners killed a few more men before it was knocked out by a shell as the infantry overran machine-gun posts and got ready for the main advance. The first two objectives were on the rise south-east of Flers and the third was on the Flers–Lesbœufs road beyond. The 41st Brigade was to take the first two and the 42nd Brigade the last. At 6:20 a.m. tank D3 drove towards Cocoa Lane, one having ditched and D5 lagged behind. Two battalions overran shell-hole positions of BIR 14, whose telephones had been cut and SOS rockets obscured; Tea Support Trench and Pint Trench were taken with many prisoners and then the Switch Line (first objective) by 7:00 a.m.[51]

Troops linked with the Guards Division on the right and formed a defensive flank on the left facing the 41st Division (Major-General Sydney Lawford) area. The two supporting battalions came up through a bombardment and suffered many casualties to shell-fire and isolated Bavarian parties. The attack on Gap Trench was forty minutes late, then troops dribbled forward and the garrison surrendered but the 41st Division was still late.[51] The 42nd Brigade moved forward by compass past Delville Wood, deployed 400 yd (370 m) short of the Switch Line and attacked the third objective thirty minutes late; the right hand battalion was stopped just short and the left hand battalion was also caught by machine-gun fire and forced under cover. The two supporting battalions got further forward and found that the neighbouring divisions had not, enfilade fire meeting every movement.[52]

The 41st Division was to attack Flers and had most tanks, four for the Longueval–Flers road and six to attack the middle and west side of the village. On the right flank the 124th Brigade attacked with two battalions forward and two in support, having assembled in no man's land. The advance began at zero hour and Tea Support Trench and the Switch Line fell relatively easily by 7:00 a.m. and Flers Trench at 7:50 a.m. At 3:20 p.m. a large party of infantry reached Bulls Road and linked with the 122nd Brigade on the left but attacks on Gird Trench failed. The 122nd Brigade had attacked with two battalions and two in support, reaching the Switch Line by 6:40 a.m. and the on to Flers Trench. Tank D15 was knocked out near the Switch Line, D14 ditched near Flers and D18 was damaged by a shell at Flers Trench but managed to withdraw. D16 entered Flers at 8:20 a.m. followed by troops of the 122nd Brigade, D6, D9 and D17 driving along the eastern fringe of the village, destroying strong points and machine-gun nests. By 10:00 a.m. the surviving Bavarians made a run for Gueudecourt and small parties of the 41st Division reached the third objective. A lull occurred from 11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. then the third objective was consolidated along with Box & Cox Trench and Hogs Head. D16 was undamaged but D6 was set on fire close to Gueudecourt; D9 got to Box & Cox, along Glebe Street where it was knocked out. D17 was hit twice by artillery-fire and abandoned on the east side of Flers and recovered later.[53]

The 2nd New Zealand Brigade (2nd NZ) of the New Zealand Division (Major-General Andrew Russell) advanced with two battalions thirty seconds early and ran into the creeping barrage. German machine-gunners in High Wood caught the troops but they were able to capture the Switch Line and Coffee Lane and dug in beyond the Switch Line by 6:50 a.m. A third battalion leapfrogged through the new line and then advanced with the creeping barrage at 7:20 a.m. and took the second objective at Flag Lane at 7:50 a.m. Two more battalions took over and captured Flers Trench and Flers Support Trench at 8:20 a.m. on the right, against small-arms fire from Flers, Abbey Road and a sunken lane. The New Zealanders had begun to dig in by 11:00 a.m. The battalion on the left was stopped by uncut wire and waited for the tanks to arrive but D10 was knocked out at Flat Trench. D11 and D12 arrived at 10:30 a.m., rolled over the wire and the infantry passed through to the last objective. Grove Alley was captured by the party withdrew at 2:30 p.m. D12 ditched west of Flers, D8 got to Abbey Road but its vision prisms were hit and D11 took guard at the Ligny road for the rest of the night.[54] In the III Corps area, the 47th Division (Major-General Sir Charles Barter) attacked on the right with the 140th Brigade whose troops reached the Switch Line and dug in on the far slope with the New Zealanders. Four tanks had also driven forward at zero hour and two reached the south end of High Wood and then turned east onto easier ground. One tank got lost and ditched in the British front line after mistakenly firing on the troops there and the second tank got stuck in a shell crater. The third tank crossed the German line in High Wood and fired into the support line until knocked out and the fourth bogged in no man's land. The Germans in High Wood defeated the attack with machine-gun fire and a mêlée began. The two battalions of the 141st Brigade advancing on the second objective at 7:20 a.m. was drawn in and on the far right flank Flag lane was captured.[55]

At 8:20 a.m. the 1/6th London moved through towards Cough Drop and a few men made it to Flers Trench but were repulsed. Cough Drop was held and attempts were made to dig eastwards to the New Zealanders. At 11:40 a.m. after a hurricane bombardment of 750 Stokes mortar bombs in 15 minutes, several hundred Germans in High Wood began to surrender as Londoners worked round the flanks and the wood was captured by 1:00 p.m. At 3:30 p.m. two battalions of the 142nd Brigade in reserve went forward to take the Starfish Line, one battalion moving to the east of High Wood and being stopped short of Starfish. As night fell, three companies advancing along the left side of the wood were also stopped and there was no consolidated front line except on the right at Cough Drop, where the 1/6th London were in contact with the New Zealand Division.[55]

In the 50th Division (Major-General Percival Wilkinson) area, the 149th Brigade attacked with two battalions, one in support and one in reserve at zero hour and by 7:00 a.m. had captured Hook Trench and gained touch with the 150th Brigade on the left. After receiving machine-gun fire from High Wood on the right at 8:10 a.m. a battalion began to bomb down trenches towards the wood and the support and reserve battalions were sent to reinforce. Just after 10:00 a.m. a battalion reached a sunken road near The Bow and another battalion set up a defensive flank north-west of High Wood and later on portions of the Starfish Line were captured. The 150th Brigade attack had two tanks advancing ahead of the infantry and one reached Hook Trench and fired into it until hit by two shells and blown up as the other tank crossed the trench drove on to the third objective and knocked out three machine-guns on the edge of Martinpuich before returning to refuel.[55]

The infantry attack took the first objective by 7:00 a.m. and reached parts of the third objective by 10:00 a.m. but one battalion retired to Martin Trench as its flank was exposed. Two reserve battalions were sent forward at 9:05 a.m. and around 3:30 p.m. German shelling forced one battalion to retreat to Hook Trench. About 100 men held a sunken road south of The Bow and the 150th Brigade was forced to abandon the Starfish Line and moved back to Martin Trench and Martin Alley by German bombardments. At 5:45 p.m. the 150th Brigade was ordered to attack Prue Trench and join with the 15th (Scottish) Division in Martinpuich. At 9:40 p.m. two battalions of the 151st Brigade attacked but were forced back by machine-gun fire and dug in, as did the third battalion, which attacked late at 11:00 p.m. and dug in after a short advance.[55]

The 15th Division (Major-General Frederick McCracken) attacked with two battalions attached from the 23rd Division and the 45th Brigade on the right flank attacked with two battalions, one in support and three in reserve. The barrage was found to be very good and little resistance was met except at Tangle South and the Longueval–Martinpuich road. The 46th Brigade on the left attacked with all four battalions and three in support and captured Factory Lane at 7:00 a.m., touch being gained with the Canadians on the left as patrols went along the western fringe of the village. A tank moved very slowly but attacked the Germans in Bottom Trench and Tangle Trench, silenced several machine-guns in Martinpuich and then returned to refuel, returning later carrying ammunition. The second tank was knocked out before reaching its jumping-off point. When the artillery lifted off the village at 9:20 a.m. both brigades sent patrols in and around 10:00 a.m. a 46th Brigade battalion dug in on the objective and at 3:00 p.m. a 45th Brigade battalion captured the north end of the village and the ruins were occupied by the 46th Brigade and outposts were established facing Courcelette. During the night, two fresh battalions relieved the front line and gained touch with the Canadians in Gunpit Trench and on the right flank touch was gained with the 50th Division at the Martin Alley–Starfish Line junction.[55]

16–17 September

[edit]In the XIV Corps, the 56th (1/1st London) Division made some local attacks and with the 6th Division fired artillery on the right flank of the Guards Division. The 61st Brigade of the 20th (Light) Division (Major-General Richard Davies) as attacked to the Guards and assembled 200 yd (180 m) beyond Serpentine Trench before capturing the third objective, part of the Ginchy–Lesbœufs road and two battalions then came up to guard both flanks with Stokes mortars and machine-guns as the Germans counter-attacked on the left flank through the afternoon. It took the 3rd Guards Brigade all morning to reorganise after the attacks the previous day and it did not attack until 1:30 p.m., without artillery support. Two battalions advanced through machine-gun fire until 250 yd (230 m) short of the objective and dug in with the left flank on Punch Trench; during the night the 20th Division relieved the Guards in a rainstorm.[56]

All of the XV Corps divisions attacked at 9:25 a.m. and on the 14th (Light) Division front the creeping barrage was poor. The right hand battalion was fired on from Gas Alley and forced under cover; west of the road from Ginchy–Gueudecourt road, the left hand battalion was also fired on from the front and the right and took cover in shell-holes. Two battalions tried to reinforce the attack but were also repulsed as was another attack at 6:55 p.m. The 41st Division attacked with the 64th Brigade attached from the 20th (Light) Division, which struggled up to the front line in a rainstorm during the night, were late and began 1,300 yd (1,200 m) behind the creeping barrage. There were many casualties from machine-guns and shrapnel shells before crossing the British front line but parties got within 100 yd (91 m) of Gird Trench. Tank D14 drove into Gueudecourt and was knocked out; the 64th Brigade reorganised at Bulls Road, where an order for another attack was too late to be followed. The 1st NZ Brigade defeated a German counter-attack along the Ligny road around 9:00 a.m. assisted by tank D11, which had stayed near the road all night. One battalion attacked at zero hour, and captured Grove Alley but the repulse of the 64th Brigade on the right led to more attacks being cancelled. D11 had advanced but a shell explosion underneath stopped the vehicle after only 300 yd (270 m); the New Zealand right was short of the Ligny road and a trench was dug back to Box & Cox.[57]

In the III Corps, a 47th Division battalion of the 142nd Brigade attacked thirty minutes early from Crest Trench towards Cough Drop 1,300 yd (1,200 m) beyond to capture Prue Trench but after passing the Switch Line, German machine-gun fire and artillery-fire dispersed the attackers who took cover in the Starfish Line except for one company which got into Cough Drop. The 151st Brigade of the 50th Division also attacked Prue Trench east of Crescent Alley and parties from two battalions briefly occupied the objective. A battalion from the 150th Brigade also attacked but veered to the left and were repulsed and attempts to bomb down Prue Trench from Martin Alley were also abortive. The 15th (Scottish) Division was counter-attacked during the morning and Martinpuich was bombarded all day. Posts were set up nearer to 26th Avenue and the line up to the Albert–Bapaume road was taken over from the Canadians.[58] By 17 September the Guards Division had been relieved by the 20th (Light) Division and on the right, the 60th Brigade was attacked and eventually managed to repulse the Germans. The 59th Brigade attacked at 6:30 p.m. in heavy rain to capture the third objective but machine-gun fire prevented an advance. The 14th (Light) and 41st divisions were replaced by the 21st Division (Major-General David Campbell) and the 55th (West Lancashire) Division (Major-General Hugh Jeudwine).[58]

18–22 September

[edit]The rain continued and turned the roads into swamps but at 5:50 a.m. in the XIV Corps area, a battalion of the 169th Brigade, 56th (1/1st London) Division attacked up the Combles road but made little progress as a battalion on the right flank managed to bomb forward slightly. The 167th Brigade was to attack the south-east face of Bouleaux Wood but was so impeded by mud and flooded shell-holes that it could not even reach the jumping-off point. A battalion each of the 16th and 18th brigades of the 6th Division attacked the Quadrilateral and Straight Trench, also at 5:50 a.m. and captured the position and a sunken road beyond. A third battalion bombed forwards from the south-east and reached the 56th (1/1st London) Division at Middle Copse. The first attack on Straight Trench failed but bombers eventually got in while a party swung left and got behind the Germans and took 140 prisoners and seven machine-guns. Signs of a counter-attack forming near Morval were seen and bombarded; the 5th Division (Major-General Reginald Stephens) began to relieve the 6th Division.[59]

The 55th Division completed the relief of the 41st Division in the XV Corps area by 3:30 a.m. and bombers of the 1st NZ Brigade bombed up Flers Support Trench close to the Goose Alley junction. In III Corps, the 47th Division sent troops of the 140th Brigade to bomb along Flers Trench and Drop Alley to their junction and parts of two 142nd Brigade battalions attacked the Starfish Line but were only able to reinforce the party already there. Later on, German bombers counter-attacked and drove back the British towards the Starfish Line and were then repulsed during the night. At 4:30 p.m. the 50th Division attacked eastwards along the Starfish Line and Prue Alley, with two battalions and bombers of the 150th Brigade and got close to Crescent Alley as a 151st Brigade battalion tried to bomb up Crescent Trench from the south. The 15th (Scottish) Division made minor adjustments to its front line and began its relief by the 23rd Division, which also took over the Starfish Line and Prue Trench west of Crescent Alley from the 50th Division.[60]

On 19 September, a battalion of the 2nd NZ Brigade bombed along Flers Support Trench towards Goose Alley during the evening as a battalion of the 47th Division moved up Drop Alley towards Flers Trench, the Londoners being pushed back to Cough Drop. The III Corps divisions continued to make local attacks and slowly captured the final objectives of 15 September with little opposition. The 56th (1/1st London) Division dug a trench north-east of Middle Copse and south of the copse sapped forward towards Bouleaux Wood. Next day the 47th Division was relieved by the 1st Division and the New Zealanders attacked at 8:30 p.m. with two battalions without a bombardment and captured Goose Alley as troops on the flank attacked up Drop Alley to meet the New Zealanders; a German counter-attack was defeated and Drop Alley was occupied up to Flers Trench. During the night of 20/21 September, patrols on the III Corps front found that the Germans had retired from Starfish and Prue trenches and in XIV Corps the Guards Division took over from the 20th (Light) Division. During 22 September, the III Corps divisions consolidated Starfish and Prue trenches and the 23rd Division found 26th Avenue from Courcelette to Le Sars empty.[61]

German 1st Army

[edit]The British preparatory bombardment began on 12 September and next day, to limit casualties the number of troops in the front line was reduced to a man for every 2 yd (1.8 m) of front and three machine-gun nests with three guns each per battalion. Each man had three days' rations and two large water bottles.[30] On the 3rd Bavarian Division front Bavarian Infantry Regiment 17 (BIR 17) was overrun and Martinpuich captured. on the left BIR 23 was able to defeat the attack on Foureaux Riegel at High Wood but was driven from the wood and the trenches from High Wood to Martinpuich later, taking up positions north and east of the village. Battalions of the 50th Reserve Regiment were sent forward and counter-attacked at 5:30 p.m. with the survivors of BIR 23 and were able to reach trenches several hundred yards from the new British front line but Martinpuich was not recaptured. After dark, the defenders improved the defences, reorganised and regained contact with flanking units ready for 16 September. The diarist of BIR 14 recorded that when the prisoners saw the supplies behind the British front, they were astonished at the plenitude, thought that Germany had no chance against such quantity and that had they had such support, they could have surpassed the British effort that day and won the war.[62]

On the 4th Bavarian Division front, Bavarian Infantry regiments 9 and 5 (BIR 9, BIR 5) in Foureaux Riegel opposite Delville Wood were quickly overrun and BIR 18 on the right flank up to High Wood was forced back. At 5:30 a.m. the British bombardment on the area back to Flers had increased to drumfire and thirty minutes later, British troops emerged from the smoke and mist. When the creeping barrage passed over, the British rushed Foureaux Riegel and then the following waves took over and advanced towards Flers Riegel. The Germans on the rear trench of Foureaux Riegel made a determined defence but were overwhelmed and tanks "had a shattering effect on the men" when they drove along the trench parapet, firing into it as infantry threw grenades at the survivors. Returning wounded alerted BIR 5 in Flers Riegel who fired red SOS flares, sent messenger pigeons and runners to call for artillery support but none got through the bombardment being maintained on the Bavarian rear defences. Foureaux Riegel had been mopped up by 7:00 a.m. when the mist began to disperse and BIR 5 could see that the attackers were under cover in shell-holes before Flers Riegel. A tank drove along the Longueval–Flers road, unaffected by small-arms fire and stopped astride the trench and raked it with machine-gun fire, drove on and repeated the process, causing many casualties. The tank drove into Flers and emerged from the north end, moving along the Flers–Ligny road until hit by a shell, the shock of the tank led to Flers Riegel being captured followed by the village.[63]

On the 5th Bavarian Division front the bombardment increased on 14 September, causing many casualties, cutting most telephone lines and destroying the front trenches until an overnight lull. The bombardment resumed early in the morning including gas shells and before dawn a thick mist rose, which with the gas and smoke, reduced visibility and around 6:00 a.m., troops of Bavarian Infantry Regiment 21 (BIR 21) near Ginchy were surprised to see three vehicles emerge from the mist, manoeuvring round shell-craters. The vehicles, with blue-and-white crosses, were thought to be for transporting wounded. Machine-gun fire was received from them and the Bavarians returned fire but the vehicles drove up to the edge of the trench and fired along it for several minutes. The vehicles drove away, one being hit by a shell and abandoned in no man's land. Soon afterwards a creeping barrage began to move towards the German defences and the German artillery reply was considered by survivors to be feeble. A wounded officer returning for treatment found that the batteries around Flers and Gueuedecourt did not know that the British were attacking because the telephone lines had been cut and visual signals had not been seen in the smoke and mist.[64]

Foureaux Riegel and much of Flers Riegel had almost disappeared in the bombardment, most dugout entrances having been blocked and most of Foureaux Riegel was captured, despite isolated pockets of resistance. Troops of BIR 21 had waited in shell-holes for the creeping barrage to pass over and then engaged the British infantry as they advanced in five or six lines. The British troops lay down and tried to advance in small groups, some coming close enough to throw grenades and one party getting into a remnant of trench. The best grenade-thrower in the regiment was nearby and won the exchange, the British being shot down as they ran back across no man's land. By 9:00 a.m. the attack had been repulsed and hundreds of British dead and wounded lay in no man's land. On the right flank, Bavarian Infantry Regiment 7 (BIR 7) either side of the Ginchy–Lesbœufs road saw skirmish lines with infantry columns behind and 20–30 aircraft circling overhead, strafing the Bavarian infantry. With little artillery support the Bavarians were pushed out of the front line and lost Flers Riegel at 11:00 a.m. and II Battalion, with the survivors of the I and III battalions took post in Gallwitz Riegel but the British advance stopped short.[65]

Beyond BIR 7, the front was defended by BIR 14, which received no artillery support despite firing SOS flares and was broken through. The battalion headquarters destroyed documents as the British approached and at one headquarters a shell blocked the dug-out and around 6:50 a.m. grenades were thrown down the steps, putting out the lights and filling the air with smoke, dust and the cries of the wounded. Soon afterwards the entrance was widened and the occupants taken prisoner. The diarist of BIR 14 wrote that British aircraft had strafed the trenches and shell-hole positions from 300–400 ft (91–122 m), causing many losses. After 9:00 a.m. officers at the regimental HQ in Gallwitz Riegel saw British infantry 1,000 yd (910 m) away, moving from Flers either side of the road to Gueudecourt and more troops advancing from Delville Wood to Flers Riegel. What was left of the regiment retreated to Gallwitz Riegel and engaged the British as they advanced downhill from Flers. Morale revived somewhat and more troops joined in, frustrating the British attacks until the British took cover in shell-holes and communication trenches, ending the attack. At 12:30 p.m. the III Battalion dribbled forward from Le Transloy into Gallwitz Riegel and on the right, BIR 5 and BRIR 5 arrived at the Flers–Ligny road, the divisional headquarters ordering that Gallwitz Riegel be held at all costs.[66]

The 6th Bavarian Division was sent forward from Le Transloy, Barastre and Caudry, reaching Gallwitz Riegel from 1:00 p.m. and at 2:30 p.m. the 4th Bavarian Division and the right flank units of the 5th Bavarian Division were ordered to recapture Flers and Flers Riegel. The attack was poorly co-ordinated, with so many units having just arrived but parts of BIR 5 and BRIR 5 advanced west of the Flers–Gueudecourt road. The British were pushed back towards Flers, with many casualties; engineer stores and a battery of field guns were re-captured. At 4:30 p.m. two tanks emerged from the village but were knocked out by artillery. The Bavarians took over Kronprinzen Weg (later Grove Alley) 400 yd (370 m) north of the village, where machine-gunners of BIR 18 arrived along with two infantry companies. Along the Ligny–Flers road, two battalions of BIR 10 counter-attacked at 5:10 p.m. into massed small arms fire from Flers and were repulsed, a battalion retreating to Gallwitz Riegel and the other to Kronprinzen Weg. East of Flers the attack was delayed and BIR 10, 11 and 14 advanced at 6:30 p.m., by 10:30 p.m. were 50 yd (46 m) from Flers Riegel and dug in around Lieber Weg (later Gas Alley). In the 5th Bavarian Division area, the remnants of BIR 7 attacked near Lesbœufs and pushed back British troops towards Flers Riegel but could not re-capture the trench. South of Ginchy, BIR 21 had defeated the attacks all day; from 6 to 7 p.m. the British resumed the drumfire bombardment until 8:00 p.m. but no attack followed.[67]

Reserve Army

[edit]15 September

[edit]

The Canadian Corps, on the right flank of the Reserve Army, made its début on the Somme next to the III Corps. The 2nd Canadian Division (Major-General Richard Turner) attacked with the 4th Canadian Brigade on the right of the Albert–Bapaume Road, three battalions to advance to the objective and the 6th Canadian Brigade attacked on the left with two battalions and one following battalion to mop-up. Three tanks were to advance up the Albert–Bapaume road to a sugar factory, which one tank was to attack as the other two turned right down Factory Lane, to the corps boundary with III Corps. On the left of the road in the 6th Canadian Brigade area, three tanks were to advance to Sugar Trench then to attack down it to the sugar factory from the north; the infantry and tanks were to begin together but the infantry were warned not to wait. The sound of the tanks moving up was heard by the Germans, who fired a slow barrage onto the rear areas and communication trenches but this turned out to be a planned raid against the 4th Canadian Brigade. German bombers attacked at 3:10 a.m. and 4:30 a.m., three of the Canadian battalions only just managing to repulse the Germans in time for zero hour at 6:20 a.m.[68]

The creeping barrage began 50 yd (46 m) from the German front line, on the left flank of the 45th Reserve Division in the area of Reserve Infantry Regiment 211 (RIR 211). II Battalion was east of the road and III Battalion was on the west side and received an overhead machine-gun barrage. The Canadians met determined resistance but within fifteen minutes drove the German infantry from the front line, the 4th Canadian Brigade reaching Factory Lane at about 7:00 a.m. and finding many German dead and wounded; about 125 prisoners were taken at the sugar factory, including a battalion headquarters and groups of snipers and machine-gunners who refused to surrender were killed. The 6th Canadian Brigade made slower progress against Reserve Infantry Regiment 210 but reached the objective around 7:30 a.m., the left-hand battalion over-running a strong point on the Ovillers–Courcelette track and up McDonnell Trench, from where machine-guns could be fired eastwards along the new front line. The Canadian attack was costly but the remainder began to consolidate and patrols maintained contact with the Germans as they retreated. On the right flank, Lewis guns were set up in the sunken road from Martinpuich to Courcelette and patrols scouted Courcelette before the British bombardment ended at 7:33 a.m. The tanks had been outpaced and one ditched short of the Canadian front line but the two that reached the sugar factory found it already captured and returned, one laying 400 yd (370 m) of telephone cable. A tank in the left group broke down but the other two reached the German trenches and killed many infantry before ditching in McDonnell Trench.[69]

On the left, the 3rd Canadian Division attacked early with the 5th Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles to secure the left flank, captured the objective and set up a block near Fabeck Graben, shooting down German troops as they fled. Further left, the 1st Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles were prevented from raiding the German lines by a bombardment; on the extreme left, raiders attacked Mouquet Farm in a smokescreen and killed fifty troops of II Battalion, RIR 212. The Canadians set up advanced posts beyond Gunpit Trench and the south fringe of Courcelette as soon as the barrage lifted at 9:20 a.m. and touch was gained with the 15th (Scottish) Division on the right. Reaching Courcelette was obstructed by German counter-attacks from the village by I Battalion, RIR 212 from reserve. At 11:10 a.m. the Canadian Corps HQ ordered the attack on the village to begin with fresh troops at 6: 15 p.m. The 22nd Battalion (French Canadian) and the 25th Battalion (Nova Scotia Rifles) arrived on time and attacked into Courcelette when the barrage lifted, occupying a line around the village, cemetery and quarry. The two battalions repulsed German counter-attacks for three days and nights (of the 800 men of the 22nd Battalion, 118 remained after three days of fighting).[70] The 7th Canadian Brigade battalions, attacking from Sugar Trench, lost many casualties to machine-gun fire and found it hard to keep direction in the shattered landscape but captured McDonnell Trench and the east end of Fabeck Graben. The brigade linked with the 5th Canadian Brigade, except for a gap of 200 yd (180 m) at the junction of Fabeck Graben and Zollern Graben.[71]